By Wu Ruoqi –

It was the usual case of the forbidden fruit being the sweetest.

The offending material in question – the folk opera “Farewell at the Inn” (小辭店) – featured as its female lead an adulteress trapped in an unhappy marriage lamenting over the impending departure of her lover and reminiscing the bliss he has given her, a storyline that naturally shocked conservative pre-1949 rural society in China.

The authority’s efforts to ban the opera only fueled demand for it. Audience still clamoured for this particular number and theater troupes delivered it accordingly. And when women who had been married for a number of years learned that “Farewell at the Inn” was being staged, they’d arrive at the theater square with extra handkerchiefs. The reason: most were miserable in their marriages, so they would cry their hearts out at lyrics like “spouse in name only without love to speak of, in the presence of an empty stove and lone candle my anguish is unbearable” (名份上是夫妻哪有什麽恩愛,對空灶守孤燈好不悲哀).

That those female peasants enjoyed watching “Farewell at the Inn” over and over again despite their familiarity with its plot caught my attention, for this would explain one thing that has confounded me about my habit of watching online news channels in Hong Kong: even when it becomes apparent at the beginning of an episode of online channel host Thomas Yan Sun-kong’s (甄燊港) expletive-filled program “China Revealed” (國情揭露) that I’m already acquainted with the material he’s about to present, I’ll still watch it, putting him on speaker and blasting out his voice at full volume. Those female peasants’ adoption of “Farewell at the Inn” as their means of release made me realise that I, too, have been using Thomas Yan as my outlet – it’s actually his swear words I crave hearing. He claims spewing obscenities is his way of expressing his frustrations at Hong Kong’s political situation. Bothered by my own negative sentiments about Hong Kong but held back by my conviction that it would be unladylike to let curse words pass through my lips, I am only too grateful to find a willing accomplice in him and vicariously “curse” through him.

I wonder if my suppression of my urge to swear is how self-censorship can feel like. If this is the case, then the nature of self-censorship is more complicated than I’d thought. I used to think one self-censors out of fear of government sanctions, that one can self-censor to get the authorities off one’s back and still maintain beliefs different from the ones being imposed on one by the authorities. If there’s a type of self-censorship that’s more like my inability to bring myself to swear, however, it means just as somewhere along the way I’ve incorporated the creed that it’s unbecoming for a woman to swear as my personal code of conduct, so somewhere along the way I’ve unknowingly allowed my value system to be co-opted by Beijing.

I’m asking myself these questions because having recently returned to Hong Kong after 10 years in China – it was there that I got my first real job and spent my most impressionable years – I now have other Hong Kong people around me as comparison, and suddenly I’m aware of these deep-seated beliefs inside me that I didn’t know exist.

HKJA reports document complaints against freedom curbs

I was intrigued, for example, to observe my reaction when, eager to learn more of the local media landscape, I browsed through Hong Kong Journalists Association’s annual reports, which read as a litany of escalating complaints against China for curbing of media freedom in Hong Kong and therefore violating the Basic Law, which guarantees such freedom.

My gut response upon reading the documents was “you mean you guys were expecting something different!”

The truth is, my decade-long stay in China has given me different reference points. Perhaps it’s because I was once hired by a company in China that had such good connections with the government that within the first few weeks into my job, I had already picked up my mainland colleagues’ habit of tossing phrases like “give a heads-up” (打招呼) and “hit the ball on the margin” (打擦邊球) in their day-to-day conversations about work – these were the stock descriptions they gave to the maneuvers they used to get government representatives to grant the company exemptions from the law; perhaps it’s because too many times I’ve been in the presence of mainlanders who would happily sign any document at the lawyer’s office and make pledges they had no intention of keeping; perhaps it’s because I’ve been repeatedly criticised by mainland superiors for being anal-retentive about procedures (你做事太按部就班). The accumulative effect of all this – and it goes without saying that what I’ve alluded to is just the tip of the iceberg – is not only have I long been inoculated against the shock of seeing the law being broken. I’m almost tempted to find fault not with Beijing but with the authors of the HKJA annual reports for expecting Beijing to observe the Basic Law (or any kind of law) in the first place.

And when I heard one of my favourite online channel hosts Lau Sai-leung (劉細良) declaring in the voice-over for his program “奪命Loudzone” that “if we resign to our fates, then we’re not Hong Kong people” (如果我地認命,就唔係香港人), it struck me how foreign this notion seemed to me. More compatible with my worldview is the whimper Cantonese opera star Hung Sin-niu (紅線女) let out to visitors at the height of the Cultural Revolution – she had just been newly released from labour camp and had had half her hair shaved – “I really believe in fate.”

But what really unsettles me is this schizophrenic state of mind I’m burdened with: a corollary of accepting China’s control of Hong Kong media as “normal” is while a number of veteran journalists still in their prime who sees China’s meddling as abnormal have fought for the right to speak freely by resigning from mainstream media and launching their own news channel on Youtube and Facebook, I can’t help but see such excursions as “illegitimate,” even as I’m writing for one of such media.

Like the female protagonist in “Farewell at the Inn,” I’m weighed down by a “conscience” that I need to constantly quell as I pursue my equivalent of an illicit relationship, and so convinced I am that there’s no way out of not thinking this way that these words she said of her moral dilemma I could have uttered myself: “I could have poured out my heart thousands of times but still stumble over my words, it’s as if I’ve boarded on a pirate ship, having started off on the wrong foot” (千訴萬訴我訴不清楚,我好比搭上了強盜船,失錯在當初).

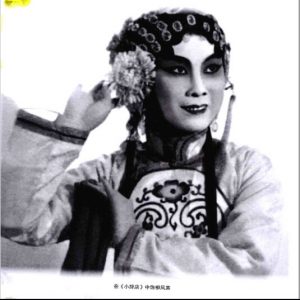

Another sign that Beijing may have infiltrated my mind is I’ve resigned myself to accepting that risks await those who work with words, that, in a way, to write is to set oneself up to be cursed. Again the female lead in “Farewell at at Inn” can uncannily illuminate what this means. That role was traditionally played by a male performer, since female artists think it would jinx them; their social status was already low to begin with, and playing a part so suggestive of sexual awakening outside marriage would only make them even more of a prey in the eyes of lecherous men. In the mid 1940’s, however, 15 year-old Yan Fengying (嚴鳳英), a clear-eyed beauty in the first flush of womanhood, arrived on the scene.

She didn’t harbour the usual reservations about “Farewell at the Inn,” having been toughened by her experience of being on her own since the age of 12 – she had fled home after her clan decided to drown her for learning and performing opera in secret. She quickly triumphed in the role, becoming so convincing in it that twice, someone in the audience saw her as fair game, abducted her and forced her to be his concubine; each time she was eventually released only after she spooked her kidnapper by attempting suicide. Her curse as a marked person persisted, though. During the Cultural Revolution, her prominence predictably made her an obvious target for persecution, and she ended up killing herself for real at the age of 38.

Yan Fengying shattered for me the illusion that writing is a solitary activity. I may be spending a good amount of time alone day in and day out figuring out the thoughts in my head, but stage those thoughts for public viewing long enough and controversially enough, and sooner or later, somewhere out there Beijing’s people will know what I know and may come up with whatever designs they have for me. Plus it probably doesn’t help that I write in English (not really my choice as I can’t write properly in Chinese). Casting China in an unflattering light in the international language has the effect of – I’m translating from a slang-laced phrase coined by another one of my favourite online channel host Yau Ching-yuen (游清源) – “showing the world what a prick Beijing can be” (柒出國際), and we all know Beijing’s feathers are even more easily ruffled when its international image is involved.

Whether Yan Fengying’s devotion to her art was worth it – whether its joys outweighed the sufferings it brought her – is a moot point, but back in the days when all those female peasants teared up as they watched her perform “Farewell at the Inn,” it must have galled some of them to see a member of their sex break down barriers while they remain too timid to opt out of their unhappy roles as dutiful wives. As for me, I may not have Yan Fengying’s daring, but I’m going out on a limb in my own way, and I’d be lying if I said I’m not taking pleasure in being naughty.

Educated at the Diocesan Girls’ School and Oxford, Wu Ruoqi lived in mainland China and worked in the PR and media sectors for a decade before returning to Hong Kong. She is now working on a book on Chinese astrology and coaching senior school students on English composition, as well as writing about the complexities of being Chinese in post-colonial Hong Kong on the side. She can be reached at [email protected]

Photo: VOHK and file pictures

Be the first to comment on "Self-censorship from a different perspective"