By Bertrand de Speville –

The ICAC is an institution, created in 1974 in the context and circumstances of Hong Kong at that time… Hong Kong has changed and is changing in many ways – economically, socially, politically. That ability to change, to adapt, to evolve is what has made Hong Kong the success that it is. The ICAC is no exception. We should not overlook an important feature of the theory of evolution. It is only the changes that are right for the environment that ensure survival. Those that are not right have the opposite effect. Again, the ICAC is no exception to this rule.

Let me mention a few of the positive changes made at the ICAC over the years.

- It used to be a highly secretive organisation where nothing was revealed unless it had to be. But for a long time now the guiding principle has been: all is transparent and open unless it has to be confidential. Confidentiality remains a vital aspect of some of the Commission’s work.

- Three of its advisory committees were chaired by the Commissioner. That changed when the workings of the Commission were reviewed by a committee chaired by Dr Helmut Sohmen in 1994. It recommended that those operational advisory committees should be chaired by a non-official member of the committee, not the Commissioner.

- The advisory committees’ activities used to be included in the Commissioner’s annual report to the Governor. Dr Sohmen’s committee recommended that they should report separately, as they have done ever since.

- Warrants of interception and surveillance are now subject to judicial supervision – an important safeguard against possible arbitrary use of those intrusive powers.

Let me turn to some of the ICAC’s features that have not changed but should have been adapted to a changed environment.

‘Wise restraint’ of leaders protects ICAC

A strange feature of the law is that it states that the Governor, now the Chief Executive, can order and control the ICAC. Section 5 of the ICAC Ordinance (ICACO) reads (as it always has):

(1) The Commissioner, subject to the orders and control of the Chief Executive, shall be responsible for the direction and administration of the Commission.

(2) The Commissioner shall not be subject to the direction or control of any person other than the Chief Executive.

These words have never presented a threat to the operational autonomy of the Commissioner simply because successive governors and chief executives have wisely exercised restraint. In the course of my work in different countries I have often been asked if the words ‘orders’ and ‘control’ did not undermine the Commission’s independence and operational autonomy. I reply that wise restraint has protected it. My questioner remains sceptical – you can see why. The words are plain enough.

The case of Peter Godber, a former British police superintendent who fled to Britain and was brought back to face corruption charge in the 1970s, had become the catalyst for the setting up of ICAC in 1974.

Why were they in the Ordinance in the first place? We must recall the context. The ICAC was a new creation with novel, extensive powers. Many were worried. No one knew how it would perform. The Administration had for years resisted the call from sections of the community to create such a body. The Governor had to be sure things would not go wrong. He therefore had to insist on being able to control his creation. In the circumstances of Hong Kong, he did not feel that accountability by means of an annual report alone was a sufficient check.

That was then. Since then, the accountability mechanisms have been increased and tightened. The exercise of some powers is subject to judicial control and supervision. The advisory committees of citizens work closely with the ICAC, monitor its activities and report separately to the Chief Executive. Prosecutions remain in the control of the Attorney General.

Time to review ICAC Ordinance

Is it not time to look at section 5 of the ICACO, a colonial relic of the those times, and allow the Commission’s operational autonomy to rest on the security of law rather than the forbearance of the Chief Executive?

Since 1 July 1997, evolution of the ICAC must take account of the provisions of the Basic Law. For instance, the appointment of the Commissioner is governed by article 48 of the Basic Law which says that the Chief Executive is ‘to nominate and to report to the Central People’s Government for appointment the …..Commissioner Against Corruption…. and to recommend to the Central People’s Government the removal of the above-mentioned official[s].’

Basic Law Article 8 says, ‘The laws previously in force in HK, that is, the common law, rules of equity, ordinances, subordinate legislation and customary law shall be maintained, except for any that contravene this Law, and subject to any amendment by the legislature of the Hong Kong SAR.’

Article 57 says, ‘A Commission Against Corruption shall be established in the Hong Kong SAR. It shall function independently and be accountable to the Chief Executive.’

In my view ‘accountable’ does not mean ‘subject to the orders and control of the Chief Executive’ in s.5 of the ICACO. The ordinary meaning of ‘accountable’ I suggest is ‘bound to give account to …’ or ‘bound to give an explanation’. It does not mean ‘bound to take orders from a person’. Nor does it mean ‘bound to be controlled by a person’.

Is there then an argument that ICACO s.5 contravenes BL 8?

But whether it does or not, the question should be asked: does the Basic Law prevent the legislature of HK considering ICACO s.5 and amending it if it thought fit? If the answer is no, it does not, how might it be amended?

The words ‘subject to the orders and control of the Chief Executive’ in S.5(1) could be deleted. Furthermore, the words ‘free from any interference’ in BL 63 (which deals with criminal prosecutions by the Department of Justice) might be added so that s.5(1) would read: ‘The Commissioner shall be responsible for the direction and administration of the Commission, free from any interference.’

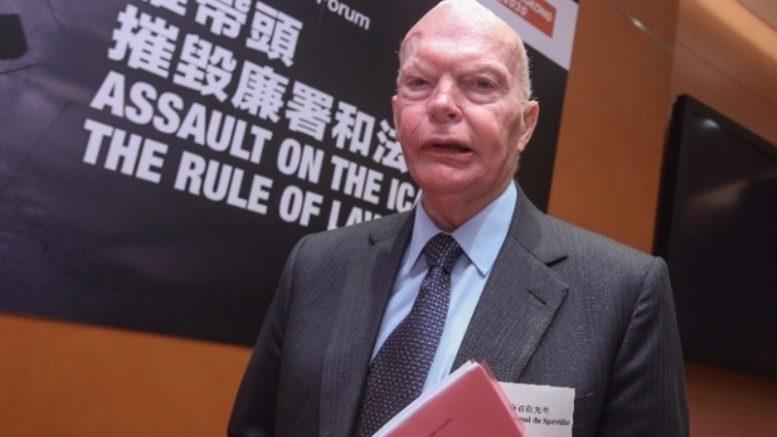

Former ICAC chief Bertrand de Speville and former chief secretary Anson Chan speak at a symposium on ICAC and rule of law.

In consequence, s.5(2) would be amended by deleting the words ‘other than the Chief Executive’ so that it would read: ‘The Commissioner shall not be subject to the direction or control of any person.’

These amendments would, it seems to me, accord with the Basic Law and would rid Hong Kong of an historical anomaly in the law that has lain in wait for more than 40 years and now threatens the survival of Hong Kong’s world-class anticorruption body. The historical reasons that justified this inroad into the independence and operational autonomy of the ICAC have long been overtaken by the checks and balances that have evolved to ensure that the ICAC is properly restrained in the use of its powers. These suggested amendments are small but significant evolutionary changes to the institution. They would not guarantee its survival but would, in my view, be a step in the right direction.

Operations head need not be deputy commissioner

Another evolutionary change that should be considered is the situation that has obtained at the ICAC from the outset, namely that the Head of Operations is always the Deputy Commissioner. In consequence, when the Commissioner is absent, the Dep Commissioner always acts as Commissioner (unless the Chief Executive otherwise directs). Since the Deputy Commissioner is, like the Commissioner, nominated by the Chief Executive, the Head of Operations tends to regard himself or herself as equivalent to the Commissioner. The self-importance of some officers of the Operations Department is made worse. It’s bad enough that the largest department should have the lion’s share of the ICACO and of the PBO and sell far more newspapers than the other two departments ever could, without having the Head of Operations also being the Deputy Commissioner. The key to success of the famous 3-pronged strategy is the equal importance of each arm and therefore the equal importance of each department – Community Relations, Corruption Prevention, and Operations. They must all pull together, like the horses of a troika, and the Commissioner’s job is to ensure they all pull in the same direction.

How then did this lop-sidedness of the Commission come about? When Jack Cater was invited to be the first Commissioner, he wanted John Prendergast as his Head of Operations. Prendergast agreed to come only if he was made Deputy Commissioner. And so it was. The law was drafted to create a Deputy Commissioner. Prendergast was appointed Deputy Commissioner and Jack Cater made him Head of Operations. The precedent was set, and has dogged the ICAC to this day. Every Head of Operations has also been the Deputy Commissioner. But the reason for this situation has long disappeared. There certainly is a need for a Deputy Commissioner to help manage an institution of, now, some 1400 established posts. But why continue the historical quirk of making the Deputy Commissioner also the Head of Operations? No change to the law would be needed – just a change in internal arrangements.

Tenure of ICAC head

The word itself in the ICAC’s title is insufficient. We need some detail to put flesh on the bare word. One of the most important details is the security of tenure of the Commissioner. It is curious that there is not a word about security of tenure in the ICACO. On the contrary the Commissioner holds ‘office on such terms and conditions as the Chief Executive may think fit.’ Apart from that, there is nothing about how long he or she is to serve. Nor is there anything about his or her removal. There never has been. It seems to be a hangover from colonial days. Is it not time to specify the term of service in office and the procedure and conditions for removing the incumbent before that term expires?

Review of ICAC, now

Originally Government felt a review of the ICAC should occur every 10 ten years. Time slipped by and it was 20 years before the Sohmen Committee was established and set to work in 1994. It reported 22 years ago. Another review I suggest is overdue. Should it not now be done?

Bertrand de Speville is former head of the Independent Commissioner Against Corruption (1993-1996). This is an edited version of his speech at the Hong Kong 2020 and the Citizens Foundation Forum entitled “Assault on the ICAC and the rule of law” held on August 13, 2016.

Photo: Pictures provided by the organisers and taken from ICAC website

Be the first to comment on "ICAC no exception for change"