By Chris Yeung —

Much has been said about the importance of continuity in Beijing’s “one country, two systems” policy for Hong Kong. Horse-racing shall continue; dancing shall continue. Capitalistic lifestyles shall remain unchanged by, and even beyond, 2047. You name it.

Against that historical background, the restructuring of the ruling Chinese Communist Party’s team in charge of Hong Kong affairs could not be more ironical. The thinking that underpins the new structure represents a profoundly-important departure from the notion of continuity.

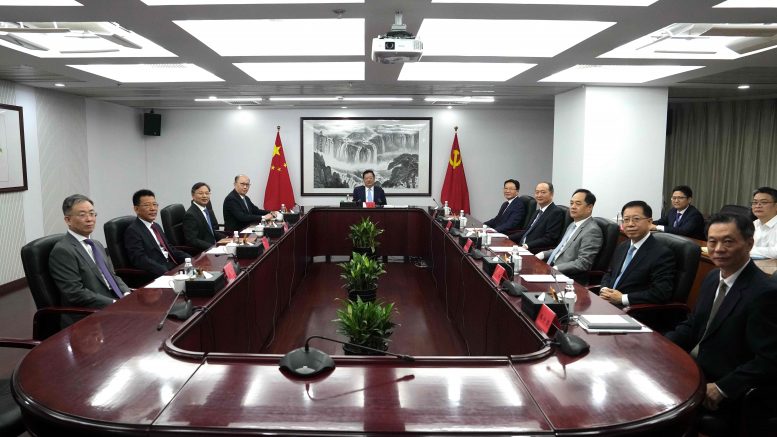

Last week, the upgraded Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office reporting directly to the Party convened its first meeting in Beijing, with Xiao Baolong continuing as director, assisted by five deputies.

A photo released by the HKMAO showed Xia chairing the meeting, with Zhou Ji (周霽), Henan’s deputy secretary and provincial security chief, and Zheng Yanxiong, director of the central government’s liaison office in Hong Kong, sitting on either side down from him.

Behind Xia are the CCP flag and the Chinese national flag.

With zero previous work experience in handling Hong Kong affairs, Xia was parachuted to head the HKMAO in February 2020, replacing Zhang Xiaoming, a longtime Hong Kong hand, who was later transferred to the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, the nation’s united front body. Zhang joined the HKMAO in the mid-1980s.

One month before Xia’s appointment, Luo Huining was named as director of the central government’s Liaison Office in Hong Kong, displacing another veteran official deeply involved with Hong Kong affairs, Wang Zhimin.

The top-level shakeup in both offices came months after opposition against the now-dead extradition bill in Hong Kong morphed into the city’s worst political turmoil since the riot in the mid-1960s.

With hindsight, it has paved the way for not just the formation of a new structure under the party overseeing Hong Kong policy, but more importantly, a total change of mindset and approach towards Hong Kong affairs.

The pool of experience of the old Hong Kong hands who straddled different generations since the 1980s had been deemed as important in maintaining continuity of Hong Kong policy in the Chinese hierarchy.

If that had been seen as an asset, it has probably been dismissed as negative assets in the wake of the political turmoil in 2019.

The months-long unrest, which was eased in early 2020 as the Covid-19 pandemic grew rampant, has emerged as the last straw on the back of the camel. Shocked and rocked by the massive civil disobedience, the communist leadership adopted a shock therapy approach to help restore order and peace and prosperity.

It features major surgery coined as “improvement” of the electoral rules (2022) and the district council system (2023) and the enactment of the Hong Kong national security law (2020).

John Lee, who joined the Government as a police inspector in the 1980s, became the Chief Executive. Pundits say the surprise elevation of Lee symbolised the beginning of “police officers ruling Hong Kong.”

Behind the series of bold, controversial moves is a sense of crisis among the party leadership about the urgency of a change of direction in its Hong Kong policy from a sit-back, hands-off approach to being more assertive, aggressive and hands-on.

The role and focus of work of the upgraded office will be shifted from “coordinating” to “giving leadership” and exercising “comprehensive jurisdictions”, which includes research and studies, supervision and implementation.

The dominating line of thinking in Hong Kong policy will be shifted from giving consideration to the historical and special conditions of Hong Kong to putting the city in the context of the nation as a whole.

It is along that line that veteran cadres with strong provincial work backgrounds such as Xia and Zhou Ji have been given a leading role in driving Hong Kong policy. Zhou attended last week’s meeting at HKMAO’s executive deputy director. He is tipped to succeed Xia as head of the HKMAO after he retires.

With the Hong Kong policy now directed by the party leadership under Xi Jinping, the Xi approach that emphasised on “dare to struggle” (敢于鬥爭) will feature more prominently in the way Hong Kong governs and tackles a litany of domestic and international issues.

They ranged from resolving deep-seated contradictions such as housing to responding to complex international situations such as human rights issues and the row over Japan’s plan to release radioactive waste water.

ends

Be the first to comment on "Change, not continuity, is Beijing’s new HK plan"