By Chris Yeung –

All eyes are on China this week. The so-called “two sessions,” namely the annual plenary sessions of the Chinese National People’s Congress, NPC, and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, CPPCC, kicked off in Beijing last Sunday and Monday separately. Stage-managed events though they are, the national plenums have and will shed some light on the latest development of the 1.4 billion-populated nation. And more important, what it means for Hong Kong and the world. This year’s “two sessions” are no exception.

There is no doubt a list of routine reports, including the government work report delivered by the Premier and others compiled by the country’s finance chief and top judge, are kind of must-read for those who are keen to know more about China. They will be tabled for a vote, or what cynics would say, being rubber-stamped by the national deputies. In addition to those reports, it is almost certain that members will also say yes to a proposal by the ruling Communist Party’s Central Committee to amend the Chinese Constitution. Scheduled to be tabled for an approval today, the proposed change, if approved, will allow President Xi Jinping to rule as head of the nation for as long as he chooses.

This is despite the fact that the move, which will effectively turn one of the most important reform initiatives taken by the late Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping into history, seems to have caused a stir among the people. Outside China, concerns about China under Xi may turn from autocracy to dictatorship are even more apparent. They fear China is moving backwards. Their fears are not unfounded.

Deng leads reform

Following the introduction of reform and open policy aimed to lift the country out of poverty in 1978, Deng started to fix the flaws in the political system. He moved to amend the Constitution to put a cap on the term of office of the State President. This was aimed to avoid giving too much power to one person if he or she can stay on the position as long as he or she likes to under the Constitution. The reform drive, coming at the end of the decade-long Cultural Revolution masterminded by Mao Zedong, has come a long way since then. Today, China is the second largest economy; it is poised to challenge the supremacy of the United States on many fronts. It is too early to say whether it will pose a serious military threat to the region and the world. But there are growing jitters in the West about China under Xi Jinping.

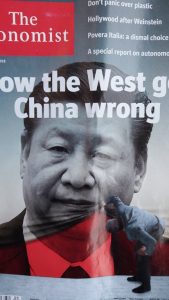

In its edition published last week, The Economist magazine put Xi on its cover, again. This time, without the costumes of an imperial emperor as it was the case a couple of years ago. It goes with graphics that raised a question about who Xi really is. Its headline read: What the West got wrong. The magazine’s verdict is bleak, saying Western countries’ bet that China would follow the path of many other countries, moving towards democracy and the market economy after it opened up, has failed. Hopes that Xi would move towards constitutional rule when he gained power five years ago were dashed. It says Xi has steered politics and economics towards repression, state control and confrontation.

With the NPC set to approve the amendment to the Constitution at the ongoing plenum, the article raises a question the West must face: What to do?

Xi reinstates life-tenure system

It is perhaps the same question that has come to the minds of many Hongkongers when they read and heard media reports about the proposed constitutional change last month. Like many in the West, they have reacted with disbelief, disappointment and perhaps disillusionment for the same reason. Isn’t that a Great Leap Backward after nearly four decades of reform and open door? If the answer is a clear yes, why? Their anxieties deepened as they reflected on what happened in the city after it became a Special Administrative Region under the “one country, two systems” political framework in 1997. The Economist’s article’s reference to “repression, state control and confrontation” has struck the raw nerves of many Hong Kong people. This is plainly because it sounds so familiar to them in the past few years with Beijing tightening its control over Hong Kong.

To be fair, there are no city-wide crackdown against political dissidents and human rights activists in Hong Kong as it happened in the mainland. Access to Internet remains free. There are increasing signs, however, the central authorities are trying to make the fullest use of their sovereign power without any restraint to dictate on how the city should be run. The fine balance between the principle of “one country” and the notion of “two systems” embodied in the letter and spirit of the Basic Law has been upset. Cases are aplenty.

One of the worst cases is the interpretation of the oath-taking provision in the Basic Law by the NPC Standing Committee last year, which came ahead of the ruling of a relevant case by a local court. On the political front, the central government’s Liaison Office, under its new head Wang Zhimin, is taking a more proactive on Hong Kong affairs, far exceeding what the name of its office, liaison, has suggested. In a striking resemblance to the penalty of stripping of political rights in the mainland’s judicial system, government officials have disqualified a student leader, Agnes Chow, from contesting the March 11 Legislative Council by-election. She lost the right to stand for election after a civil servant ruled the political party she belongs to advocates self-determination.

Hopes dashed

Like the West, Hong Kong people have put a bet on a China seeking to catch up following decades of political chaos and economic woes after Britain handed back the city to China in the 1984 Joint Declaration. They hoped the differences between the city and the hinterland would have been narrowed down as the reform drive deepened and broadened. With Hong Kong moving towards full democracy after 1997, democracy would have landed on the mainland, albeit in a slower pace. The bet has failed. The promise of democracy enshrined in the Basic Law has become a pipe dream, among other promises.

On the face of it, both Hong Kong and the West are losers in their bet on China. The ruling communist party, however, will be the biggest loser if their success in economic reform and opening up has failed to bring about progress towards a free, open and democratic China.

Chris Yeung, Chief Writer of newly-launched CitizenNews, is founder and editor of the Voice of Hong Kong website. He is a veteran journalist formerly worked with the South China Morning Post and the Hong Kong Economic Journal. He writes on Greater China issues.

This is the full text of his Letter to Hong Kong broadcast on RTHK Radio 3 on March 11.

Photo: VOHK pictures

Be the first to comment on "Hong Kong loses bet on China"