By Chan King-cheung –

Hong Kong saw two large-scale riots since 1949. First it was the “Double Tenth Riot” erupted on October 10, 1956. It lasted for about one month, leaving 60 people dead, more than 300 injured. More than 1,000 people were arrested. After the Riot, the then Hong Kong governor Sir Alexander Graham had sent a report on the riot to the colonial office in London on December 23, 1956, giving a detailed account of what and why it had happened.

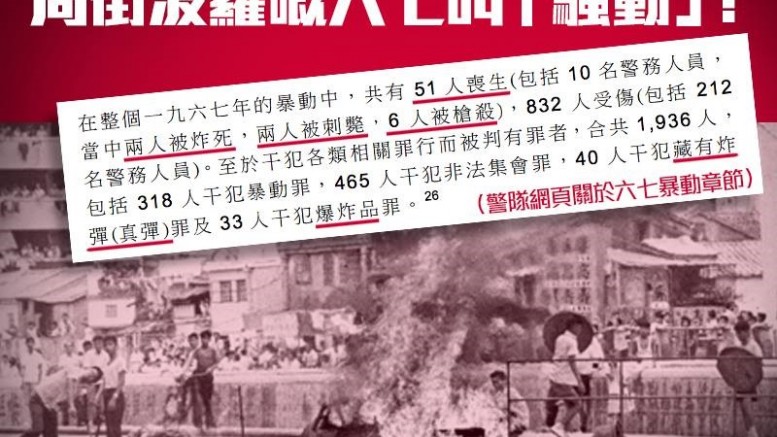

Then came the 1967 Riot. First sparked by a labour dispute at a artificial plastic flower factory in San Po Kong, it turned swiftly into a large-scale demonstration and confrontation in streets. The riot had dragged on for more than one year. 51 people died. Several thousands of people were injured. Following the 1967 Riot, the government had implemented a series of reforms in areas including housing, youth and public transport. In 1974, the Independent Commission Against Corruption was established.

That the two riots had lasted for more than one year is because there were strong political forces behind them. They had participated fully in various aspects including organisation, planning and support, making it difficult to put an end to the disturbances within a short period of time.

In its report on “Double Tenth Riot”, the then government fingered at triad elements for attempting to disrupt public order for sinister motives. But it is open secret that the real “black hands” had intricate ties with Taiwan’s Kuomintang. The report had avoided mentioning it. As for the 1967 Riot, there are documentation evidences that show it was directly led and backed by the mainland authorities.

Put simply, the two riots would not have brought such serious consequences if not for the involvement of the two parties, namely the Kuomintang and the Chinese Communist Party.

Governance strategy will change

Compared with the two riots, the possibility of the Mongkok disturbances the Government has branded as riot evolving into a larger-scale conflict is not high unless there are evidence showing clearly there are political forces behind it. The incident, however, has become more serious after the Chinese Foreign Ministry has branded groups that participated the “riot” as “separatist organisations.” Following the official remarks, rioters have been classified as “separatist”. The nature of their “crime” is not long merely hinged upon criminal offence, but crimes involved national security.

Will the official stance on the conflict affect the way Hong Kong deals with demonstrators? The State Council has published a white paper on “one country, two system” published on July 1, 2014. Some commentators have said one of the objectives of the policy document is to enhance vigilance against the growth of “pro-independence, separatist forces.” The Foreign Ministry’s comment on the riot is in line with the State Council’s position in the white paper, targeting at “separatist forces.” Undoubtedly, the Hong Kong government will take a hardened approach in dealing with the Mongkok riot.

Localist groups have upgraded the level of violence in their political struggle. The mainland authorities have responded in a hardened approach by “upgrading” the classification of the riot as separatist. What impact the standoff will make?

In the wake of the Mongkok clash, the governance strategy in Hong Kong will definitely change. A lot of friends are worried about the Hong Kong scene, but have no clue of what is in store. Many Hong Kong people are asking: where Hong Kong is going to?

Chan King-cheung is a veteran journalist. He writes on political and economic issues in Hong Kong and China. This article was translated from his regular column in the Chinese-language Ming Pao.

Photo: Picture taken from DBC Select Facebook

Be the first to comment on "Where Hong Kong goes after Mongkok ‘riot’"