By Dora Choi Po-king

Two cases of infringement of academic freedom in Hong Kong after 1997 have led to greater awareness in the academic community and the society about the importance of academic freedom. There is no better time than now to re-open our examination of academic freedom by revisiting incidents..

The “Robert Chung Incident” in 2000

In July, 2000, Dr Robert Chung, director of the Public Opinion Polls programme at HKU, published articles in 2 local newspapers, alleging indirect interference on the part of the then Chief Executive, Tung Chee-hwa, who had wanted to discontinue his polls on the CE and the SAR government. Chung’s allegations, and his further disclosure of the role of “middle persons” (namely, Prof Wong Siu-lun, Pro Vice-Chancellor, at the behest of the Vice Chancellor, Prof Cheng Yiu-chung) who had told him of the CE’s “displeasure” concerning his public polls, set off a public outcry.

The Council of HKU promptly set up a three-person Independent Investigation Panel headed by Justice Noel Power, which conducted an 11-day open hearing in August. The Panel’s report, released in early September, found that Prof Wong had indeed conveyed a message from the VC to Dr Chung, which was “calculated to inhibit his right to academic freedom.” Prof Cheng and Prof Wong eventually resigned from their positions.

Following this investigation, HKU also set up a Senate Task Force on Academic Freedom to collect opinions from staff and students regarding academic freedom. Its report in 2002 offered a working definition of academic freedom, in addition to a full-page list of freedoms and responsibilities on the part of the institution as well as members of the university. More significantly, this report highlighted a possible danger of limitation of this freedom and autonomy by the government, particularly its “functional arms” such University Grants Committee and Research Grants Committee.

The HKU task force’s report also insisted the university’s accountability “is to the norms of free and open pursuit of knowledge, not a kind of obedience to either political or academic authority.” It also contained a strong rebuttal of the Sutherland Report on higher education in Hong Kong. In The Sutherland Report had observed that academic freedom, in particular, institutional autonomy, should be “redefined” in face of the growing strength of private or corporate wealth, as well as political power. The HKU report pointedly said that these are “dangerous remarks, apparently politically motivated”, which confused moral and legal rights.

The HKU Council nevertheless adopted the recommendations for the restructuring of governance in the Sutherland Report in a later review (Fit for Purpose Report, 2003). As Petersen and Currie (2008) observed, the Sutherland Report had a highly deleterious effect on academic freedom and institutional autonomy in higher education in Hong Kong.

In all the eight publicly-funded institutions, formerly elected deans of faculties are now replaced by appointed ones, who, in turn, appoint heads of departments. It results in a situation that the VC, with a significantly expanded central management team, heads a descending order of executives all the way down to the academic departments. Coupled with this is a much smaller, “streamlined” governing Council (in all higher education institutions with the exception of CUHK), which therefore allowed greater domination by non-university members.

This restructuring of governance, as Petersen and Currie (2008) observed, dovetailed with stricter regulation by the UGC through frequent quality assurance and accountability exercises, thereby enabling it to quickly “impose its own ethos of managerial governance.” Of course, one must also not forget that all UGC members are appointed by the CE. The incident at Hong Kong Institute of Education showed the UGC was effectively an arm of government control, instead of a buffer between government and universities as originally envisioned.

The “HKIEd Storm” in 2007

A controversy erupted after the then Vice President of the Hong Kong Institute of Education (HKIEd), Prof Bernard Luk, published an open letter in the HKIEd Intranet, subsequently carried in Ming Pao on July 5, 2007. Luk revealed how the Institute’s Council, with over half of its members being appointed by the CE, high-handedly imposed a strictly business mode of personnel appointment and salary structure, thereby causing great upheavals and instability. Another revelation, which immediately sent shockwaves through the academic community and the general populace, was that Arthur Li, the then Secretary for Education and Manpower, had made several calls to Prof Paul Morris, President of HKIEd, pressurizing him to initiate a merger of HKIEd and the Faculty of Education, CUHK.

In a subsequent inquiry ordered by the then Chief Executive Donald Tsang Yam-kuen, it was revealed that Li had even once used the word “rape” when he threatened to ask the then permanent secretary for Education and Manpower, Fanny Law Fan Chiu-fun, to cut the total number of students at HKIEd.

Li had also threatened Prof Luk, who was then Acting President, saying “I’ll remember this. You’ll pay.” Luk was said to have refused to issue a public statement to condemn the escalating protests of “surplus teachers” and the Professional Teachers’ Union. Lii’s strongly-worded comments came as no surprise. The Commission has noted in their report Li, on assuming the ministerial post, had already used words such as “the authority is in my hands”, and “starting with diplomacy and following with deployment of a troop (權在我手,先禮後兵), when he talked about his strategies to push for university mergers.

Luk also revealed that Mrs Fanny Law had made calls to the Prof Morris, expressing her displeasure over newspaper articles written by teachers of HKIEd and vowing to “get rid of them”. It emerged in the Inquiry that she had also called one of the teachers to reprimand him over his newspaper articles that criticized education reforms and policy, as well as over the invitation of a guest speaker to a seminar.

The Commission’s Report, published in June 2007, found that Fanny Law had expressed her opinions to her critics in a manner of “intimidation and reprisal”, and that her behavior constituted “improper interference with their academic freedom.” On the other hand, although the Commission has accepted that Arthur Li had used the word “‘rape’ to express the official decision that HKIEd had to merge with CUHK, and (it) should better cooperate”, and further, that he had verbally “suggested” (threatened) Prof Morris that a Government Committee be set up to look into the status of HKIEd, ranging from university status to being disbanded, it nevertheless ruled that the allegation that Li had threatened to allow Fanny Law to cut student numbers at will did not stand. The reason was that it did not see any “concerted effort to force HKIEd to agree to a merger with CUHK by improperly reducing the student numbers of HKIEd in order to make it ‘unviable’.” About Li’s threat to Prof Luk (You’ll remember this, etc), the government’s attorney believed that Li “was likely to have said the offending sentence, … in which case (he) would have made an improper threat” . However, such words might just be “innocent representations in a casual conversation” Moreover, the Commission observed that “it seems to be (Li’s) style or habit to introduce metaphors or other literary devices to season the effect of what he said. In a highly emotive state, he might have used words which were intended to dramatize speech.”

The Commission, in a full chapter, discussed institutional autonomy and the nature of university education, which is directly relevant to our concern about political interference today. It saw the government as the guardian of public interests, and as such, it stipulated that it “is entitled to encourage, steer, or direct HEIs (higher education institutions) in accordance to its policy and public interest” as long as there is transparent and thorough consultation.

HEIs are reminded that they do not enjoy “absolute immunity from justified intervention from a stakeholder” and that they should not place “institutional or ‘sectoral’ interest before their collective social responsibility.” This is all very well, except that the Commission held the view that in this era of “globalization, the commodification of knowledge, and the market force in the educational market”, institutional autonomy is no longer an absolute value to be protected. Hence the government is entitled to “take steps to ensure that” HEIs respond to the market.

This is a highly controversial point, to say the least, and the Commission’s unquestioning acceptance of the merit of academic pursuit and university education being overtly responsive to market needs to be challenged. Even more dangerous, however, is its insistence on the government’s role in steering universities towards this direction.

Two observations

In light of the two landmark cases, there are two observations about the state of institutional freedom and academic freedom in Hong Kong. Justice Hartmann, in his Judgment over the judicial review sought by the then Secretary of Education, Michael Suen Ming-yeung over a fine point in the 2007 Commission Report, stated that whether a threat by a senior government official constituted a real threat depends very much on the context. Let me turn to the wider context then.

First, power is highly centralized in the ruling polity, and the SAR government is not properly accountable to the citizens of Hong Kong. Mechanisms for open and free elections to the legislature and the CE office are not in place, and heads of the various secretariats are appointed by the CE, who is not responsible to society.

In higher education institutions, a significant number of the members of Council are directly appointed by the government, constituting a direct threat to institutional autonomy, as Petersen and Currie (2008) has argued. The developments in these past few years indicated that the CE has even attempted to micro-manage the universities, via his position as Chancellor of universities. It is in this context that Tung Chee-hwa could still vouchsafe the “honesty” of Andrew Lo after the HKU investigation in 2000, and that Arthur Li could remain in his office as Secretary of Education after the Commission of Inquiry accepted that “there were a number of areas in which Prof Li’s evidence was found wanting in terms of credibility.”

It is also in this context that we must see the heavy dominance of the UGC as an arm of government to control and regulate research and education in universities today.

Secondly, it is in this context of centralized power that one should view and appreciate the actions of whistleblowers. Thanks to Robert Chung, Bernard Luk, and, Fung Jing-en, student representative at the HKU Council, we got to know the underhand deals, the direct interference into academic freedom, and the insolence of government officials and pro-government members in university management. Of course, in this same context, these brave individuals are penalized, sometimes heavily. For the sake of surer guardianship of public interest, not to mention greater fairness and justice, perhaps it is time we raise the issue of whistleblower protection legislation.

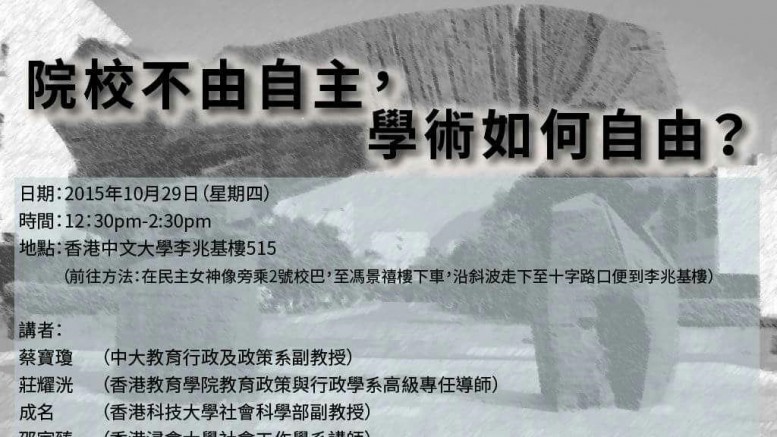

Dora Choi Po-king, Associate Professor at the Department of Educational Administration & Policy of Chinese University of Hong Kong, is also Co-convenor of Scholars’ Alliance for Academic Freedom. This is an edited version of her speech given at the Alliance’s seminar held on October 29, entitled “No academic freedom without institutional autonomy.”

Photo: VOHK Picture

Be the first to comment on "Institutional autonomy key to academic freedom"